RESEARCH PAPER

Risk screening for HIV testing in Zimbabwe: a qualitative study

1

Department of Primary Health Care Sciences, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe

2

Ministry of Health and Child Care, AIDS and TB Unit, Harare, Zimbabwe

3

Organization for Public Health Interventions and Development (OPHID), Harare, Zimbabwe

4

Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), Harare, Zimbabwe

Submission date: 2023-03-22

Final revision date: 2023-08-30

Acceptance date: 2023-11-23

Online publication date: 2025-07-15

Corresponding author

Hamufare Dumisani Mugauri

The University of Zimbabwe, Department of Primary Health-care Sciences, Harare, Zimbabwe

The University of Zimbabwe, Department of Primary Health-care Sciences, Harare, Zimbabwe

HIV & AIDS Review 2025;24(3):234-241

KEYWORDS

TOPICS

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

The use of screening tools for targeted human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing improves efficiency by identifying individuals, who are likely to test positive. Effective utilization of screening tools needs an understanding of healthcare workers (HCWs) and willingness to use these tools. In this study, health workers' perspectives on screening tools were determined to augment their effective and consistent utilization.

Material and methods:

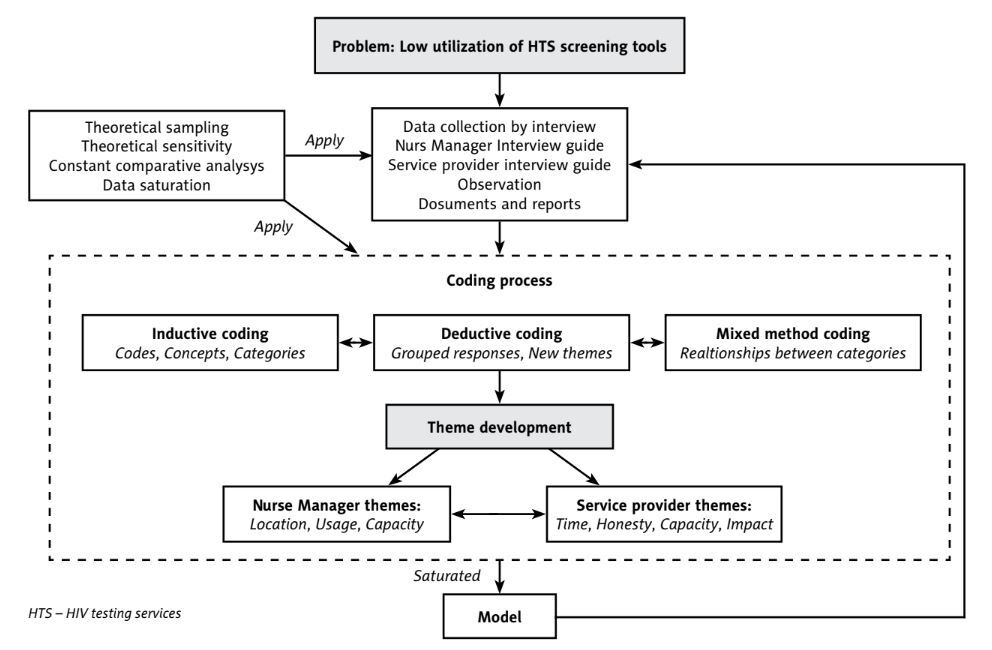

A qualitative study among HCWs at eight selected primary healthcare facilities in Zimbabwe was conducted. Interviewer-guided, in-depth interviews were performed with HCWs and their immediate supervisors. Inductive and deductive coding (hybrid) was applied to develop and analyze themes following a framework built around the grounded theory model to describe perspectives, which influence effective and consistent utilization of HIV screening tools as well as suggestions for enhanced eligibility screening.

Results:

Behavioral factors facilitating the application of a screening tool included motivation to adhere to standard practice, awareness of screening role in targeting testing, and its ability to manage workload through screening out ineligible subjects. This was apparent across all service delivery levels. Barriers included limited healthcare capacity, lack of confidentiality space, multiple screening tools, obscure screening in/out criteria, and the possibility of subjects not responding to screening questions truthfully.

Conclusions:

Across all geographical and service delivery levels, the correct placing of screening tool at HIV testing entry points and HCWs knowledge on screening in/out criteria, emerged as the key factors for correct and consistent utilization of screening tools. Standardization of the tools would improve their appropriate choice and utilization.

The use of screening tools for targeted human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing improves efficiency by identifying individuals, who are likely to test positive. Effective utilization of screening tools needs an understanding of healthcare workers (HCWs) and willingness to use these tools. In this study, health workers' perspectives on screening tools were determined to augment their effective and consistent utilization.

Material and methods:

A qualitative study among HCWs at eight selected primary healthcare facilities in Zimbabwe was conducted. Interviewer-guided, in-depth interviews were performed with HCWs and their immediate supervisors. Inductive and deductive coding (hybrid) was applied to develop and analyze themes following a framework built around the grounded theory model to describe perspectives, which influence effective and consistent utilization of HIV screening tools as well as suggestions for enhanced eligibility screening.

Results:

Behavioral factors facilitating the application of a screening tool included motivation to adhere to standard practice, awareness of screening role in targeting testing, and its ability to manage workload through screening out ineligible subjects. This was apparent across all service delivery levels. Barriers included limited healthcare capacity, lack of confidentiality space, multiple screening tools, obscure screening in/out criteria, and the possibility of subjects not responding to screening questions truthfully.

Conclusions:

Across all geographical and service delivery levels, the correct placing of screening tool at HIV testing entry points and HCWs knowledge on screening in/out criteria, emerged as the key factors for correct and consistent utilization of screening tools. Standardization of the tools would improve their appropriate choice and utilization.

REFERENCES (24)

1.

UNAIDS. Global HIV Statistics. Fact Sheet 2021 [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/reso... (Accessed: 30.09.2023).

2.

UNAIDS 2022. Global HIV Statistics [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/reso... (Accessed: 14.07.2023).

3.

UNAIDS GAN. Global AIDS Update: Confronting Inequalities [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/reso... (Accessed: 30.09.2023).

4.

Ministry of Health and Child Care, Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Population-based HIV impact assessment 2020 (ZIMPHIA) [Internet]. Zimbabwe Population-based HIV Impact Assessment. ZIMPHIA 2020. Final Report; 2020, p. 71.

5.

UNAIDS World AIDS Day Report 2020. Prevailing Against Pandemics by Putting People at the Centre [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/reso... (Accessed: 30.09.2023).

6.

Routine and Targeted HIV Testing [Internet]. Available from: https://www.thebodypro.com/art... (Accessed: 10.02.2022).

7.

Ministry of Health and Child Care, Zimbabwe National HIV Testing Services Strategy, 2017-2020 [Internet]. 2017; Available from: https://hts.hivci.org/hts-scor....

8.

Ong JJ, Coulthard K, Quinn C, Tang MJ, Huynh T, Jamil MS, et al. Risk-based screening tools to optimise HIV testing services: a systematic review. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2022; 19: 154-165.

9.

Mugauri HD, Chirenda J, Takarinda K, Mugurungi O, Ncube G, Chikondowa I, et al. Optimising the adult HIV testing services screening tool to predict positivity yield in Zimbabwe, 2022. PLoS Glob Public Health 2022; 2: e0000598. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000598.

10.

Charmaz K. Grounded theory: methodology and theory construction. In: International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Elsevier; 2001, pp. 6396-6399.

11.

Ministry of Health and Child Care, Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Operational and Service Delivery Manual (OSDM) for the Prevention, Care and Treatment of HIV in Zimbabwe, 2017 [Internet]. 2017. Available from: http://www.ophid.org/treat-all... (Accessed: 09.12.2020).

12.

Ministry of Health and Child Care, Zimbabwe. National AIDS Council. Zimbabwe HIV and AIDS Strategy for the Informal Economy 2017-2020 [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/africa/cou... (Accessed: 08.09.2020).

13.

Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract 2018; 24: 9-18.

14.

Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, Pölkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngäs H. Qualitative content analysis: a focus on trustworthiness. Sage Open 2014; 4: 215824401452263. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/215824....

15.

Wong L. Data analysis in qualitative research: a brief guide to using Nvivo. Malays Fam Physician 2008; 3: 14-20.

16.

Sirinskiene A, Juskevicius J, Naberkovas A. Confidentiality and duty to warn the third parties in HIV/AIDS context. Med Etika Bioet 2005; 12: 2-7.

18.

Konradsen H, Lillebaek T, Wilcke T, Lomborg K. Being publicly diagnosed: a grounded theory study of Danish patients with tuberculosis. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2014; 9: 23644. DOI: 10.3402/qhw.v9.23644.

19.

Sauka M, Lie GT. Confidentiality and disclosure of HIV infection: HIV-positive persons’ experience with HIV testing and coping with HIV infection in Latvia. AIDS Care 2000; 12: 737-743.

20.

Deribe K, Woldemichael K, Wondafrash M, Haile A, Amberbir A. Disclosure experience and associated factors among HIV positive men and women clinical service users in Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2008; 8: 81. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-81.

21.

Liu GG, Guo JJ, Smith SR. Economic costs to business of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Pharmacoeconomics 2004; 22: 1181-1194.

22.

Bloom DE, Glied S. Benefits and costs of HIV testing. Science 1991; 252: 1798-1804.

23.

Howard J. HIV screening: scientific, ethical, and legal issues. J Leg Med 2018; 252: 1798-1780.

24.

Leiner S. Screening for HIV, diagnosis and treatment. N Engl J Med 1988; 318: 378-380.

We process personal data collected when visiting the website. The function of obtaining information about users and their behavior is carried out by voluntarily entered information in forms and saving cookies in end devices. Data, including cookies, are used to provide services, improve the user experience and to analyze the traffic in accordance with the Privacy policy. Data are also collected and processed by Google Analytics tool (more).

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.